Distinct somatic genome variations in young lung cancer patients

Lung cancer in young adults is relatively rare, but it is considered a unique subgroup with distinct biology [1]. In patients aged ≤ 40 years, the incidence of lung cancer has been found to be 4 % [2], and in those aged ≤ 45 years, 5.3 % [3]. Characteristically, women are more often affected than men; adenocarcinoma prevails, and the stage of disease is frequently advanced at the time of the diagnosis. Of course, these patients usually receive aggressive treatment.

According to recent studies in young lung cancer patients, actionable genomic targets such as EGFR and ALK aberrations might be more enriched in this population [2]. There was also a trend with regard to HER2 and ROS1 alterations. Hsu et al. found no significant difference in survival between young lung cancer patients with and without EGFR mutation [4]. However, the broader genomic landscape and related oncogenic pathways are not fully understood yet.

Overlap with TCGA genes

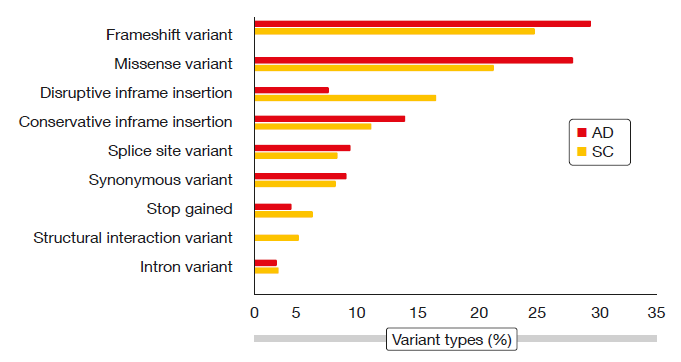

Therefore, Wu et al. performed whole exome sequencing based upon paired normal blood DNA and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded genomic DNA in 27 Chinese NSCLC patients aged ≤ 45 years (median, 40; range, 31–45) [5]. Adenocarcinoma was present in 18 patients, and 21 were female. All of them had never smoked or did not smoke at the time of diagnosis. The investigators identified adenocarcinoma (AD) and squamous-cell carcinoma (SC) somatic variants, ending up with 288 and 151 AD and SC variants, respectively. Among genomic variant types, frameshift variants and missense variants predominated in both AD and SC (Figure). For both histologies, insertion or deletion polymorphisms (indels) were present in approximately 60 % and SNPs in approximately 40 %. The majority of mutated genes in both cohorts overlapped with the mutated genes obtained in the young NSCLC The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort for each disease subtype (i.e., 86 of 94 AD mutated genes and 41 of 48 SC mutated genes).

Genes with predicted high-impact mutations were selected for the pathway analysis, which yielded somatically altered candidate pathways that differed across histologies. For example, ERK/MAPK signaling and PTEN cell cycle arrest were altered in AD, but not in SC. Conversely, this was true for Trk/PI3K signaling and ADP ribosylation/DNA repair, among others, in SC, but not in AD. Further bioinformatic analyses are ongoing to compare the mutated genes and pathways in young patients with older TCGA cohorts.

Figure: Genomic variant types in young patients with adenocarcinoma (AD) or squamous-cell

carcinoma (SC) of the lung

REFERENCES

- Luo W et al., Characteristics of genomic alter-ations of lung adenocarcinoma in young never-smokers. Int J Cancer 2018 Apr 18. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31542. [Epub ahead of print]

- Sacher AG et al., Association between younger age and targetable genomic alterations and prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2(3): 313-20

- Zhang J et al., Multicenter analysis of lung cancer patients younger than 45 years in Shang-hai. Cancer 2010; 116(15): 3656-3662

- Hsu CL et al., Advanced non-small cell lung cancer in patients aged 45 years or younger: outcomes and prognostic factors. BMC Cancer 2012; 2012 Jun 13; 12: 241

- Wu X et al., Whole exome sequencing (WES) to define the genomic landscape of young lung cancer patients (pts). J Clin Oncol 36, 2018 (suppl; abstr 12005)