EGFR-mutant lung cancer: sequencing as a major topic in light of new data

Long-term results with osimertinib after EGFR TKI failure

The first-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR TKIs) erlotinib and gefitinib as well as the second-generation EGFR TKI afatinib are the recommended first-line options for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC [1]. Regardless of the extent of initial response, however, more than 60 % of patients develop the T790M resistance mutation [2]. The third-generation EGFR TKI osimertinib, which is selective for both activating EGFR mutations and EGFR T790M resistance mutations, has recently been approved in the USA and Europe for the treatment of patients with advanced, T790M-positive NSCLC. In the two pivotal phase II AURA extension and AURA2 studies, patients with T790M-positive NSCLC following disease progression on prior EGFR TKI treatment benefited from osimertinib therapy with regard to ORR and PFS [2, 3].

At the ESMO 2017 Congress, Mitsudomi et al. reported long-term follow-up and OS data from the pooled analysis of the AURA extension and AURA2 trials [4]. A total of 411 patients had received osimertinib 80 mg/d until progression or study discontinuation. At the time of data cut-off, median duration of osimertinib treatment was 16.4 months. Median OS and PFS were 26.8 and 9.9 months, respectively, and ORR was 66 %. Median duration of response amounted to 12.3 months. Forty-one percent of patients had new lesions by investigator assessment at data cut-off, the most common sites being lung (13 %), CNS (8 %), bone (7 %) and liver (7 %).

Of 301 patients who progressed on osimertinib, 221 (73 %) continued treatment with a median treatment duration of 4.4 months. After discontinuation of osimertinib, 69 % of patients received other anti-cancer therapies. This analysis also confirmed the manageable safety profile of osimertinib, with very low rates of grade ≥ 3 AEs. In total, 4 % of patients discontinued treatment due to possibly causally related AEs.

FLAURA: first-line osimertinib

After osimertinib had been established as an effective treatment option in the T790M-mutated lung cancer setting, the FLAURA trial evaluated the first-line use of this agent in patients with advanced NSCLC harbouring activating EGFR mutations (i.e., exon 19 deletion or L858R mutation) [5]. FLAURA had a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised phase III design. In the experimental arm, 279 patients received osimertinib 80 mg/d, while medication in the control arm (n = 277) consisted of either gefitinib 250 mg/d or erlotinib 150 mg/d. Two thirds of control patients were treated with gefitinib. The enrolment of patients with stable central nervous system (CNS) metastases was allowed, as well as crossover to open-label osimertinib upon central confirmation of disease progression and T790M positivity. PFS according to RECIST 1.1 based on investigator assessment constituted the primary endpoint.

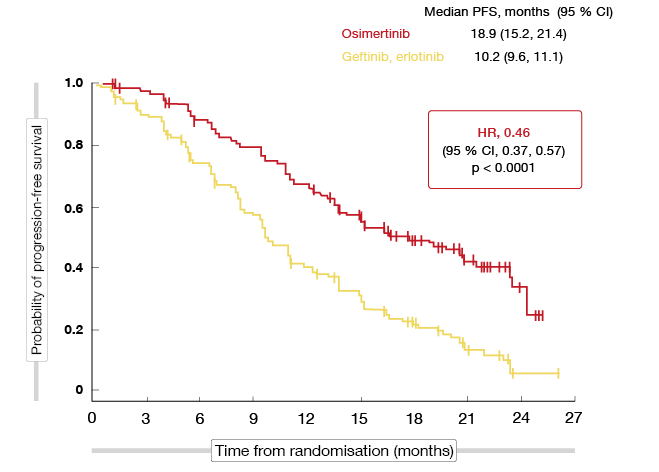

Compared to the control group, the osimertinib-treated arm experienced a significant improvement in PFS (18.9 vs. 10.2 months; HR, 0.46; p < 0.0001; Figure 1) that represented a 54 % reduction in the risk of progression or death. The PFS curves separately early on and remained separated throughout the course of treatment. All of the subgroups derived more favourable PFS outcomes from osimertinib treatment than from the first-generation EGFR TKIs.

Figure 1: Primary endpoint of the FLAURA study: progression-free survival with osimertinib vs. gefitinib and erlotinib

Doubling of duration of response

The analysis according to the presence of brain metastasis at baseline showed a consistent PFS benefit across the entire cohort: for patients with CNS metastases, PFS was 15.2 vs. 9.6 months (HR, 0.47; p = 0.0009), and for those without CNS metastases, 19.1 vs. 10.9 months (HR, 0.46, p < 0.0001). CNS progression events occurred in 6 % vs. 15 % in the whole group.

Objective response rates did not differ significantly between the two arms (80 % vs. 76 %; p = 0.2335), but osimertinib gave rise to a doubling of the duration of response (17.2 vs. 8.5 months). At the time of the analysis, median OS had not been reached in either arm, although the curves hinted at an advantage of osimertinib (HR, 0.63). The p value equalled 0.0068; at current maturity, a p value of < 0.0015 was required for statistical significance as determined by the O’Brien-Fleming approach.

The safety profile of osimertinib was comparable to the safety profiles of gefitinib and erlotinib, although with lower rates of grade ≥ 3 AEs (34 % vs. 45 % for osimertinib and gefitinib/ erlotinib, respectively) and a lower discontinuation rate (13 % vs. 18 %). Stomatitis occurred slightly more often with osimertinib, whereas acneiform dermatitis and elevations of transaminases showed comparably lower rates. Based on these results, the authors concluded that osimertinib is a new standard of care for first-line therapy of patients with EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC.

Criticism of FLAURA

In his discussion of the results of the FLAURA trial, Tony Mok, MD, Chinese University of Hongkong, China, pointed out that FLAURA is undoubtedly a positive study showing a significant benefit of first-line osimertinib, but posed the question of whether all EGFR-mutation–positive patients should indeed receive first-line osimertinib [6]. Several shortcomings of the trial design are calling for caution. For one, afatinib was not used as a comparator despite being a standard of care. Moreover, FLAURA did not clearly demonstrate the CNS activity of osimertinib, as the PFS advantage observed in patients who presented with brain metastases at baseline reflects systemic PFS rather than intracranial PFS. The presence of CNS lesions was not a stratification factor, which led to a slight imbalance in prevalence between the two groups (19 % and 23 % in the osimertinib and control arms, respectively), and CNS imaging was not mandatory for all patients. Thus, researchers did not assess intracranial CNS response in a prospective fashion. In addition, results obtained with gefitinib and erlotinib were pooled in the control arm, even though their CNS penetration rates are known to be different.

As Dr. Mok noted, the ultimate goal of lung cancer treatment is OS prolongation by optimal sequencing of effective agents. Survival in both arms of the FLAURA trial remains uncertain, as OS data for osimertinib are immature and 64 patients in the control arm are still receiving either gefitinib or erlotinib, which means that they might switch to osimertinib later on. The impact of the crossover to osimertinib is not reflected, as only 62 out of 213 patients who progressed received second-line osimertinib to date. Finally, resistance mechanisms and potential treatment strategies for patients who have failed first-line osimertinib treatment are currently unclear. Various targetable mutations are under investigation, but effective treatments still need to be established.

Data on sequencing from the LUX-Lung trials

In the phase III LUX-Lung 3 and 6 studies, treatment-naïve patients with stage IIIB/IV EGFR-mutant NSCLC were randomised to either afatinib or platinum-doublet chemotherapy [7, 8]. Compared to chemotherapy, afatinib significantly improved PFS and ORR in these trials. OS was significantly prolonged in the subgroup whose tumours had deletion 19 [9]. Patients included in the phase IIb LUX-Lung 7 trial, on the other hand, received either afatinib or gefitinib in a randomised manner. They significantly benefited from afatinib with regard to PFS, time to treatment failure, and ORR [10]. No OS difference was observed between the two arms [11].

Sequist et al. conducted a retrospective analysis of subsequent therapy outcomes in patients with common EGFR mutations in LUX-Lung 3, 6 and 7, with the aim of contributing to establishing the optimal treatment sequence for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC [12]. Among 579 patients with common mutations randomised to afatinib, 553 had discontinued afatinib treatment at the time of analysis. Seventy-one percent of these received subsequent any-line treatment, which was mostly platinum-based chemotherapy (50 %), first-generation TKI monotherapy (34 %), single-agent chemotherapy (33 %), or other treatments (22 %). The proportion of patients treated with subsequent therapies is similar to that observed in trials of other EGFR TKIs [13, 14]. There was no relevant difference in treatment duration across deletion 19 and L858R EGFR mutational subgroups.

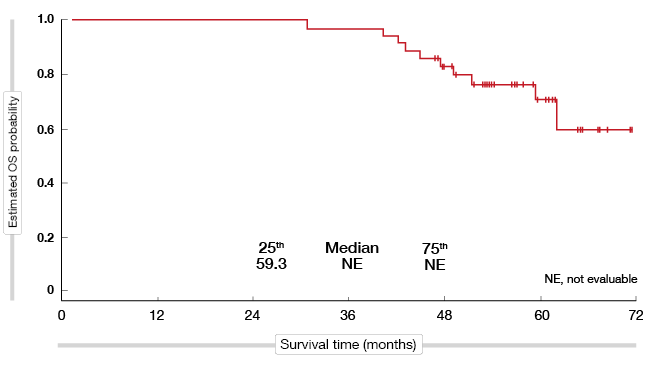

A total of 37 patients who discontinued afatinib received subsequent osimertinib, mostly in the third-line setting and beyond. For these patients, median time on osimertinib in any treatment line was long at 20.2 months, and after a median follow-up of more than 4 years, OS had not yet been reached (Figure 2).

According to the authors, these encouraging outcomes suggest that further investigation of this treatment sequence in a larger cohort is warranted. Overall, these findings support treatment sequencing with first-line afatinib followed by subsequent therapies, including osimertinib.

Figure 2: Exploratory analysis of survival in patients starting on afatinib treatment who received subsequent osimertinib in any line

References

- Novello S et al., Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(suppl 5): v1-v27

- Yang JC et al., Osimertinib in pretreated T790M-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: AURA study phase II extension component. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 1288-1296

- Goss G et al., Osimertinib for pretreated EGFR Thr790Met-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (AURA2): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 1643-1652

- Mitsudomi T et al., Overall survival in patients with EGFR T790M-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with osimertinib: results from two phase II studies. ESMO 2017, abstract 1348P

- Ramalingam SS et al., Osimertinib vs. standard-of-care EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment in patients with EGFRm advanced NSCLC: FLAURA. ESMO 2017 Congress, abstract LBA2_PR

- Mok T, The winner takes it all, ESMO 2017 Congress, Discussion of abstract “ Osimertinib vs. standard-of-care EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment in patients with EGFRm advanced NSCLC: FLAURA. ESMO 2017 Congress, abstract LBA2_PR”

- Sequist LV et al., Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3327-3334

- Wu YL et al., Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 213-222

- Yang JC et al., Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 141-151

- Park K et al., Afatinib versus gefitinib as first-line treatment of patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (LUX-Lung 7): a phase 2B, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 577-589

- Corral J et al., Afatinib (A) vs gefitinib (G) in patients with EGFR mutation-positive (EGFRm+) NSCLC: updated OS data from the phase IIb trial LUX-Lung 7 (LL7). Ann Oncol 2017; 28(suppl_2): ii28-ii51

- Sequist LV et al., Subsequent therapies post-afatinib among patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC in LUX-Lung (LL) 3, 6 and 7. ESMO 2017 Congress, abstract 1349P

- Wu Y-L et al., First-line erlotinib versus gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: analyses from the phase III, randomized, open-label, ENSURE study. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1883-1889

- Maemondo M et al., Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 2380-2388

More posts

ALK-positive NSCLC: updates on crizotinib and alectinib

PROFILE 1014 was the first study to define the role of the ALK inhibitor crizotinib in the first-line treatment of patients with ALK-positive lung cancer. It compared crizotinib 250 mg twice daily (n = 172) with pemetrexed plus cisplatin (n = 171) in patients with ALK-positive, locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic non-squamous NSCLC in the first-line setting.

Characteristics and outcomes for SCLC arising from transformation

A low but significant proportion of EGFR-mutant adenocarcinomas transforms to SCLC at the time of acquisition of resistance to EGFR TKI therapy. Moreover, cases of de novo SCLC harbouring EGFR mutations have been reported. As the clinical characteristics and clinical course of SCLC-transformed EGFR-mutant lung cancer are largely unknown, Marcoux et al. retrospectively reviewed the records of 16 patients with EGFR-mutant SCLC treated between 2006 and 2017.

Reaching unprecedented outcome dimensions in malignant mesothelioma

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare but aggressive cancer with poor prognosis. While combination chemotherapy with platinum and pemetrexed with or without bevacizumab is a standard in first-line treatment, no approved second-line strategies have been established to date. Gemcitabine or vinorelbine are often used in this situation, but these only show limited activity.

Interview: “Survival is the result of multiple treatment lines”

FLAURA is a positive trial, as its results favour osimertinib over gefitinib and erlotinib. Now we have to consider this among the multiple options that are available for the first-line treatment of EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Besides osimertinib, there are the first-generation TKIs erlotinib and gefitinib and the second-generation TKI afatinib, but maybe sometime soon also dacomitinib, for which data were presented at the last ASCO Meeting.

EGFR-mutant lung cancer: sequencing as a major topic in light of new data

The first-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR TKIs) erlotinib and gefitinib as well as the second-generation EGFR TKI afatinib are the recommended first-line options for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Regardless of the extent of initial response, however, more than 60 % of patients develop the T790M resistance mutation.

Randomised findings on CT-based follow-up after resection of early NSCLC

Regarding the optimal follow-up after surgery for early-stage NSCLC, the ESMO guidelines recommend patient surveillance every six months for 2-3 years with visits including history, physical examination and preferably contrast-enhanced spiral chest CT at 12 and 24 months. Thereafter, annual visits including history, physical examination and chest CT should be performed to detect second primary tumours (SPCs).